Don't Experiment on Your Team

The difference between understanding a framework and owning it. And how to close that gap before you inflict it on your team.

After World War II, something strange happened in the South Pacific. Indigenous communities who had watched military operations during the war started building their own airstrips. Wooden control towers. Straw planes. Men with coconut headphones waving landing signals at empty skies.

They had observed that airstrips brought cargo. So they built the airstrips to get their own cargo. Of course, the planes never came.

Anthropologists called it a cargo cult. The rituals were perfect reproductions. What was missing was understanding why.

The book-on-a-plane problem

You’ve probably read a book that genuinely excited you, something that really clicked. A framework that made you think: this could actually help my team.

But then you never did it, because you’ve seen how this usually goes.

A leader reads a book on a flight home. Lands excited. Monday morning, the announcement: “We’re doing this now.” The team dutifully goes through the motions. Quiet abandonment by Q3. Next year, it’ll be a different book from the same airport shop.

That leader forced everyone to build the runway, but never delivered the cargo.

You don’t want to be that leader. You’ve been on teams where it happened. You remember the eye-rolls, the theatre, waiting for this one to pass like the others. You don’t want to inflict that on your team.

But you also actually believe this framework could help. So what do you do?

Ritual without understanding

The problem isn’t the framework. These things work brilliantly where they come from. The problem is extraction. Taking the visible ritual without the system it lives inside.

MVP without the learning loop is just shipping something crappy. L10 meetings without the rest of the Entrepreneurial Operating System is just a rigid meeting format. Radical Candor without the caring is just being a dick.

The leaders who become cargo cult enthusiasts haven’t done the work to internalise what they’re implementing. They can talk about the idea of the framework, but not how. They can attempt the ritual, but they don’t actually know why. It’s meeting room Kabuki theatre.

How to actually internalise a framework

The challenge is that these ideas can be hard to practice outside of an organisation, so you are learning while implementing. Change requires conviction, and it can be difficult to have conviction when you need to check the manual every 10 minutes.

For some things, that’s just how it is, and why specialised consultants make a lot of money. But for others, you can apply it to your own life. Not as a thought experiment, but as an actual thing.

The goal isn’t to become an expert. It’s to build fluency.

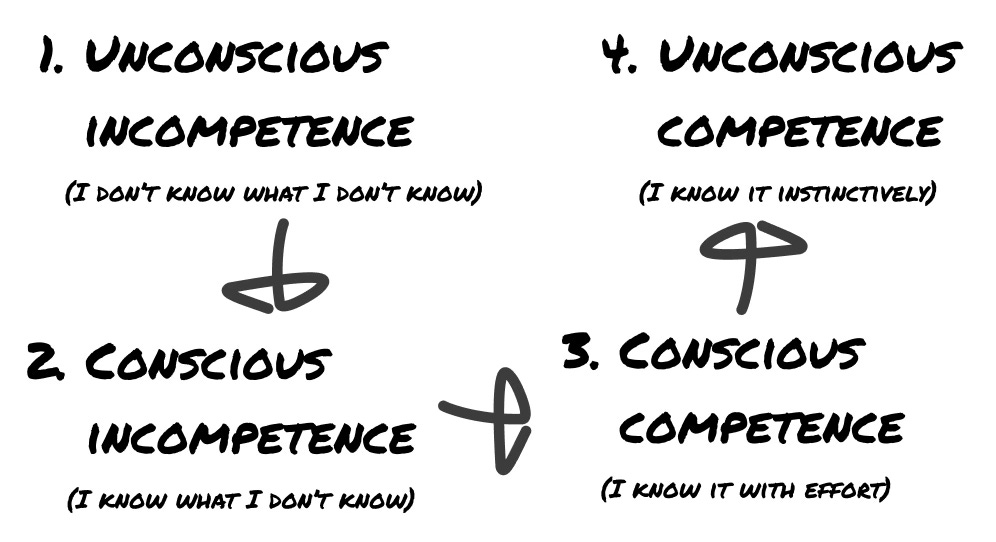

There’s a model in learning theory called the Four Stages of Competence. You start unconsciously incompetent (you don’t know what you don’t know), then become consciously incompetent (you realise you’re bad at this), then consciously competent (you can do it, even if it takes effort), and finally unconsciously competent (it’s instinctive).

Most cargo cult leaders try to implement frameworks while they’re still in the first or second stage. They’ve read the book, so they think they understand it. But they haven’t actually done the thing. They’re not even consciously competent yet, they’re just consciously aware that the framework exists.

With personal practice, you can get to stage three. You’ve actually done it. You’ve hit the awkward parts. You know where it’s hard, because you’ve struggled with it yourself. You don’t need to be an expert, you just need to have actually been through it once.

Solo practice won’t make you a master. It gets you to stage three - competent enough that the framework isn’t consuming your attention. Stage four only comes from leading real teams through real situations. But that’s the point of practicing at home: you want your brain free for the people, not the process.

When someone asks “why do we do it this way?” you can answer from experience, not from a half-remembered chapter.

OKRs are a good place to start, if you’re not using them already. Absolutely set them for the gym, but only if you actually care about failing at it. Add more as well. A side project. A skill you’ve been avoiding. Something with stakes.

At some point, you’ll realise you’re doing it wrong. Maybe it turns out your Key Results are just a to-do list. Maybe they’re too binary, one slip and the whole quarter feels broken. Whatever your failure mode is, better to get the feel for it on your sofa than in front of your team.

Other frameworks you can try on yourself

OKRs aren’t the only thing that translates to personal use.

Playing to Win works for any significant life decision. Considering a career move? Run through the five questions. What’s your winning aspiration? Where will you play? How will you win? What capabilities do you need? The stumble: you’ll discover that “Where to play” and “How to win” feel like the same question until you’ve actually tried to answer them separately. That confusion is stage two. Working through it is stage three.

Shape Up teaches you the difference between appetite and estimates. Appetite is a budget for how much time you’re willing to spend. Estimates are guesses about how long something will take. Most people confuse them. Try setting an appetite for a personal project: “I’ll spend ten hours on this, total.” You’ll feel the pull to expand when you hit the edges. The stage three moment is when you actually cut scope to fit your appetite instead of expanding the budget. That’s when you stop estimating and start shaping. A leader who’s done that once won’t cargo cult a deadline.

Jobs to be Done works when you turn it inward. Next time you’re about to make a purchase or a big decision, ask yourself: what job am I actually hiring this to do? Why do I really want this? The stumble: your first answer is almost always the surface reason, not the real one. Getting past that - learning to ask “why” until you hit something true - is the skill that makes JTBD interviews actually work.

Social frameworks need a beta tester

Not everything can be practiced solo. You can’t do Radical Candor in a room by yourself. You can’t run a Five Whys without someone to interrogate.

For social frameworks, you need a beta tester. A spouse. A peer. A coach. Someone who’ll let you practice on them before you try it on your team.

If you can’t have a Radical Candor conversation with your partner about the dishes without it blowing up, you have no business trying it on your direct reports. The stumble is the same, you just need a safer place to have it.

The difference

When you’ve lived a framework, you stop cargo culting. You understand the nuances the book glossed over. You know where it breaks. You can answer skeptical questions instantly, because you’ve already asked them yourself.

That instant response is what kills the cargo cult vibe. A leader who isn’t fumbling through the “how” can focus entirely on the team’s “why.” You’re not announcing something you read. You’re sharing something you know.

That’s the difference between building a runway and actually knowing what brings the cargo.